The US Fish and Wildlife Service is seeking comments on how the agency should direct grizzly bear recovery in the Lower 48. Read the PDF at the bottom of this page to inform your comments!

Make your comment here. The comment period closes Monday, March 17th.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Demographic information like population and inhabited range in this article refer to grizzly bears in the Lower 48 States unless otherwise stated.

Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) are one of the great symbols of the American West, synonymous with wildness and might—and they are still threatened.

Since the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) first listed them in 1975, they have also been synonymous with Western politics, and their legal status continues to fuel debate.

In early 2025, thanks to many of your comments, the USFWS decided to keep grizzly bears listed as threatened in the Lower 48. They also announced a process to redefine how they manage the species in the Northern Rockies.

That announcement (and the accompanying rule-making process) has good and bad elements. Ultimately, their primary aim is to prevent grizzly extinction. So how do you do that?

When a species is listed as threatened or endangered, federal agencies often create rules and regulations to protect them. The Endangered Species Act is explicit about the scope of these protections and clear about the imperative to prevent extinction for every species.

However, removing protections, or "de-listing" has been less obvious. This ambiguity has plagued wildlife policy for decades, including for grizzly bears.

Some argue that grizzlies are already recovered, and so should be removed from protections. If you compare grizzly bear populations and occupied range between 1960 and present day, they argue, there are some reasons to be optimistic; populations in the Lower 48 have increased by 50% and grizzlies have expanded their range.

This is misleading. Presenting the information this way sets the baseline at 1960, when grizzly bears were nearly extinct. Prior to Euro-American settlement, there were an estimated 30,000 grizzly bears in the Lower 48.

Instead of comparing today to when grizzlies were almost extinct in 1960, let's compare today to when they were abundant in 1750. Using the same numbers, grizzly bears have increased from 2% of their 1750 population... to 3%.

Is a 1% increase "recovery"? Is that "restoration"? Is that reason enough to open up trophy hunting?

This context is vital to any discussion about grizzly bear recovery. For the last several decades, Western bureaucrats and their corporate constituents have argued that grizzly bears are fully recovered and must be removed from the Endangered Species List. Their reasoning relies on the baseline of 1960, when grizzlies were nearly limited to only Glacier and Yellowstone National Park.

It also ignores that humans are still responsible for 85% of grizzly bear fatalities while they are currently protected.

The best available research suggests that grizzly bears need a connected population of 3,000 to 5,000 in the Northern Rockies to ensure their survival for centuries to come.

Isolated populations of grizzly bears pose long-term risks. In Yellowstone National Park, whitebark pine trees, an important food source for grizzly bears, have all but died out. In Glacier National Park, berry production has become erratic with climate change. In the Selkirk and Cabinet-Yaak ecosystems, roads, recreation, and black bear hunting have kept those populations extremely small and genetically at risk of in-breeding.

Because of these pressures, as well as lethal "management" by wildlife agencies, it is very unlikely that the current population and distribution of bears is sustainable in the long run.

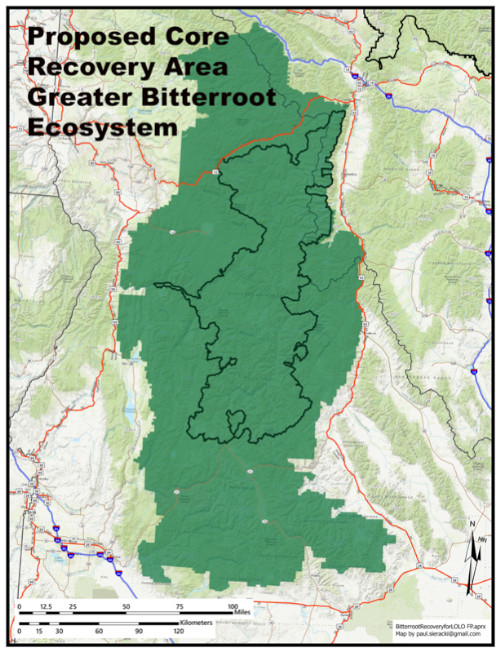

The vast wildlands of Central Idaho could provide a massive benefit to grizzly bears. One Montana grizzly bear researcher calls it the "grizzly bear promised land". This vast wild country could support hundreds of bears, and act as a genetic link between grizzlies in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (near Glacier Nat'l Park) and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Simply put, there is no "recovery" of grizzly bears in the Lower 48 until Idaho gets its bears back.

Claiming that a few hundred grizzly bears living outside national parks constitutes full recovery is bogus. Likewise, aiming for 30,000 grizzly bears in the American West is impossible (at least without a lot of zoos).

So what is a meaningful goal for grizzly recovery in the Northern Rockies?

Friends of the Clearwater, along with a diverse coalition of public lands and wildlife advocates, has outlined what that might look like. We've condensed a lot of science and policy into a vision for the sustainable management of grizzly bears.

This vision aims for meaningful policy in the Northern Rockies to ensure grizzly survival. Some of the more tangible points include:

And more. It's time to stop advocating for below the "bear minimum". We need to think big, act fast, and make sure that real protection can become law of the land.

You can read our vision in the embedded PDF below, open it in a new tab, or download it at the bottom of this page.

New-vision-for-grizzly-bear-recovery-in-the-northern-rocky-mountains-FINAL