Old timers might call this Defender’s Species Spotlight the fisher cat. But the fisher (Pekania pennanti) is not a cat, nor does it eat fish. It might better be called the porcupine-eating weasel, and is one of the rarest carnivores in the Clearwater Basin.

Conservation status: Pacific populations are threatened; Northern Rockies populations are not listed.

Fishers are cat-sized carnivores closely related to pine martens and wolverines, adapted to the northern forests of North America. They are adept at climbing trees in search of prey or to escape larger predators. Fishers are solitary generalists, roaming the forest in search of any prey they can get their paws on, primarily squirrels, rabbits, hares, mice, and porcupines.

Porcupines are the most infamous of fisher’s prey. Fishers seem to be the only common predator of the needle-armored rodents, so much so that timber companies have re-introduced fishers to reduce porcupine impacts on saplings. Fishers aggressively target the porcupine’s face—the only part of its body without quills—until it dies and can be dismembered. For large prey, fishers will store pieces of their prey in caches to finish eating later.

Fishers live in closed-canopy forests. They tend to live in lower elevations than pine martens or wolverines. Like other wild carnivores, their presence is an indicator of ecological health. While fishers in the American Northeast seem to be expanding, populations in the Pacific ranges and Northern Rockies are in decline.

Fishers are solitary except during mating season in spring. Gestation, however, is delayed until the next February, nearly a whole year. After a 50-day gestation, females give birth to one to four kits. Like other weasels, fishers use two dens, giving birth in one and moving the kits to a different den to raise their young. Dens are usually in hollow trees, so older forests are key for denning habitat. Kits are altricial, born blind and wholly dependent on their mother. After about seven weeks, kits open their eyes. They feed only on milk for eight to ten weeks before weaning. At five months old, juveniles are forced out on their own.

Wolverines and the Latin American tayra are the fishers closest relatives, all of which are part of subfamily Gulonidnae, which includes martens and the sable. Fossil records seem to show that American mustelids evolved in Eurasia and dispersed several times over land bridges.[1]

The earliest conclusive fisher fossil was found in the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in Oregon.[2] That fossil, a portion of an upper jaw and several teeth, is around 7 million years old. According to researchers, the fossil had larger teeth than today’s fishers, more closely resembling the teeth of present-day wolverines.

Trappers and farmers killed off most fishers in the 19th and 20th centuries, the former to sell fur and the latter to protect poultry. Prior to White American settlement, fishers occupied the boreal forests of Canada, the Pacific Coast forests, the Northern Rockies, and the Eastern hardwood forests as far south as Georgia. However, they were extirpated in the US south and had dramatic range reductions elsewhere. According to some researchers, fisher populations are now growing in New England and Eastern Canada, where some mature hardwood forests have recovered. In the early 2000s, fishers were reintroduced into Tennessee.[3]

On the West Coast, the Pacific subspecies of fisher is at risk of extinction.[4] Old-growth logging continues to reduce their habitat and rodenticide (both legal, as used on tree farms, and illegal, as used in marijuana farms) has led to increased mortality. The Pacific fisher used to roam from western Washington south into California; today two isolated populations exist in the Klamath-Siskiyou region and the southern Sierras. Reintroductions have taken place at Olympic and Mount Rainier National Park in Washington State.[5]

Fishers in the Northern Rockies do not have the protections of their West Coast counterparts. Fishers are one of the most elusive carnivores of the Clearwater and their exact population in the Northern Rockies is uncertain. For decades, it was believed all fishers in North Idaho and northwest Montana were descended from reintroduced animals; genetic research in 2006[6] showed that there was a small population of fishers in the Clearwater and Bitterroot mountains that was never extirpated. That genetic group, or haplotype, is unique to Clearwater country.

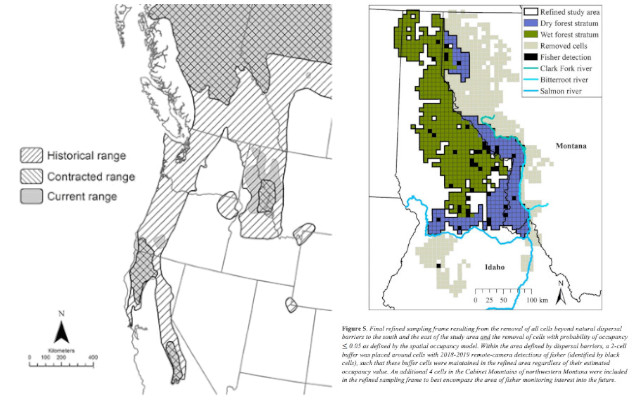

Research in Idaho in 2019 shows that those fishers in the Clearwater and Bitterroot are isolated from fishers in the Cabinet and Purcell ranges further north[7]. A larger hair-trap study between Idaho Fish and Game and Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks assessed fisher occupancy in Idaho and Montana in 2020[8].

Habitat loss is the primary threat to Idaho’s fisher population, due to logging in mature and old-growth forests. The U.S. Forest Service overarching goal to clearcut North Idaho’s mesic pine-fir forests and replace them with ponderosa-larch plantations is not compatible with fisher survival, based on fisher’s preference for older, taller, structurally complex forests.[9] Rodenticide use, especially on private timberlands, may be a problem as well. Incidental trapping of fishers in Idaho as well as vehicle collisions[10] have been documented. Wildfire may harm fisher populations, though this is based on models and not first-hand data.[11]

The Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the US Fish and Wildlife Service to list the Northern Rockies fisher as endangered in 2009 and 2013 (supported by Friends of the Clearwater and other groups).[12] The USFWS declined to list both times. As of 2025, fishers can still be legally trapped in Montana, and their habitat continues to be targeted for clearcutting across the region.

Other work referenced:

https://www.science.smith.edu/departments/Biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-156-01-0001.pdf

https://northcascades.org/pacific-fisher/

https://thefurbearers.com/blog/the-fisher-pekania-pennanti

https://idfg.idaho.gov/species/taxa/18029

[1] https://bmcbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7007-6-10

[2] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2013.722155#d1e541Species Fisher.doc

[3] https://www.chattanoogan.com/2001/11/7/14644/Elusive-Fishers-Make-Quiet-Return-to.aspxSpecies Fisher.doc

[4] https://www.fws.gov/species/fisher-pekania-pennanti

[5] https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/nature/fisher-reintroduction.htm

[6] https://doi.org/10.1644/06-MAMM-A-217R1.1

[7] https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~jacks/Lucid.Fisher.2019.pdf

[8] https://fwp.mt.gov/binaries/content/assets/fwp/conservation/wildlife-reports/8-mfwp-fisher-study-annual-report-2020.pdfSpecies Fisher.doc

[9] https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/download/52272.pdf

[10] https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/7380879

[11] https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/64266

[12] https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/mammals/fisher/

Friends of the Clearwater

PO Box 9241

Moscow, ID 83843

(208) 882-9755